My friend Susan wrote, “Although I am ashamed to admit it….I don’t think I have any goals right now. At least there are none that have crystallized for me. I am a goal-setter, always have been, and have achieved almost all that I have set….

My friend Susan wrote, “Although I am ashamed to admit it….I don’t think I have any goals right now. At least there are none that have crystallized for me. I am a goal-setter, always have been, and have achieved almost all that I have set….

What I am trying to do is feel comfortable being in the moment of my life, my career, my health…I know all too well that none of those important ‘issues’ are unchanging. Tomorrow I may lose my job, my health or even my life. I am unsure of my role in my current job, but at the moment I am enjoying it. So…is it a problem to feel goal-less in my life and career? Am I being less productive than I could be? How is being goal-less affecting my work…?

Susan’s questions touch on many important issues.

What exactly is a goal and why are goals important?

According to the dictionary, a goal is: the object of a person’s ambition – an aim – toward which effort is directed. We set goals for things we want to be different in the future, not for what we are currently satisfied with. By their very nature, goals are future-oriented.

A myriad of research studies[i] have demonstrated that goals are important because they help us get what we want, keep us from drifting aimlessly, and that people with clear goals are more satisfied.

But goals are not what’s most important.

Goals are actually guideposts, milestones that mark the way. They help us navigate the road that fulfills our needs and connects us with our hopes and desires. When we are clear about what we truly desire, goals can help us get there.

Although we can never really control our future, if we understand our priorities, our values and what’s most important, we can adapt our goals to help get us where we really want to go. [ii]

What kinds of goals do you tend to set?

Usually we set goals to help fill a need – something we want in the future that we don’t have now. The kinds of goals we set depend on what needs and desires are most pressing. Abraham Maslow, a seminal contributor to understanding motivation described a hierarchy of needs, implying they are developmental in nature.[iii] But as Susan has quite articulately described, our needs can change. Health can become an issue unexpectedly, and what Maslow considered a lower level need suddenly becomes a primary need.

Current research has focused on two types of goal-orientation – performance (achievement) and learning (mastery). Some people gravitate more toward one type or the other, although it’s also thought that one could be motivated by both. [iv] And when we set goals, most people focus on these.

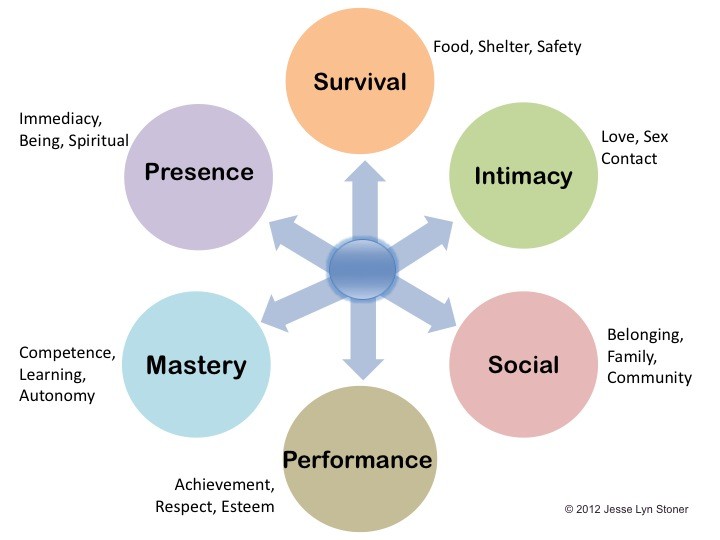

Six Goal Genres

It might be more helpful to consider your goals from the perspective of six genres. They are not linear, hierarchical or developmental. None is more important than another. At various points in your life, depending on your circumstances, any one of the six genres of goals might emerge as most pressing.

What do you do when your habitual Goal Genres no longer serve your needs and desires?

It’s likely that Susan is used to focusing on certain genres of goals that are no longer necessary for her, given her current level of accomplishment and competence. This is not an uncommon experience for highly accomplished men and women who are in the throws of mid-life.[v]

I’ve observed that as we grow older, the things we held as goals, whether we accomplished them or not, are not as compelling.

Presence: The Missing Goal Genre

Susan wants “to feel comfortable being in the moment of my life.” And here’s where her confusion comes in. Without an understanding of this Goal Genre, she believes she is goalless.

Most of us have had an experience, a moment when you know you HAVE everything you need, …where you know you ARE everything you need to be …and that there is NOTHING you need to do.

It might be at the birth of your child or when making love with someone you deeply love, or just simply a moment while floating on a raft in a pond on a warm, sunny summer day, or sitting on a porch and watching the sunset until the sky fades from dark purple to black, …and you realize I could die at this moment and I wouldn’t regret a thing. You feel alive and vibrant and it is enough.

The interesting thing about these moments is they don’t require you to climb a mountain, parachute from a plane, or go on an African safari. They occur when we deeply connect with our present experience, whatever it is.

Usually these moments are fleeting, but for some very lucky people, these moments can last for a long time.

When we reside in the moments of perfection, our typical future-oriented goals seem absurd. You have no goals because each moment is perfect. You have arrived.

HOWEVER… When you are not residing in that state of perfection, and when it is what you most deeply desire, you do have a goal – to recapture that state of Being.

The Challenge of the Presence Goal Genre

Ironically, you can’t approach goals in the Presence Genre in the same way you have learned to do so successfully in the other genres. Nature plays a trick on us. Paradoxically, using our future-oriented goal-setting skills that work so well in the other genres to return to the state of Presence can have a reverse effect.

These special moments exist exactly because we are not future-oriented. Instead of trying to control or achieve, we are accepting and appreciating.

But there is good news. It doesn’t mean you can’t have goals for this genre. They just need to be a little different.

- You can have a goal to live your life to its fullest – to be present to each experience as it unfolds, whether it is happiness or pain, joy or loss.

- You can have a goal to be true to your nature.

- You can have a goal to love yourself and to be as kind to yourself as you are to others, which means forgiving yourself when you have been judgmental, unkind, unloving or disconnected.

- And you can have a goal that when you do fall off the path, to recognize it as soon as possible so you can return.

- You can have a goal to learn to meditate so you can learn to discipline your thinking.

- You can have a goal to participate in experiences that help you lead from within.

- You can have a goal to connect with people who understand and share these goals.

Caveat – take these goals seriously but treat them lightly. Do not turn Presence into a project, because you will be approaching it from the Mastery or Achievement genre and as they say, “you can’t get there from here.”

Thanks! This is very clarifying….

Glad it was helpful. Sorry about the Pats. Hope you’re feeling better soon.

I completely agree that Susan is not without goals, she just wasn’t allowing them to be defined as goals.

In general, I think the optimal scenario is to live in the present while also working towards longer-term goals. However, as you mentioned, this can be very challenging!

I’m glad you mentioned meditation, because this has been the best way for me to live in the present. Over the past four years or so, I have meditated most mornings. And my life is so much better because of it.

Hi Greg, I like your goal of living in the present while working toward longer-term goals.

I also appreciate your recommendation for setting up a regular meditation practice. These structures help us achieve our goals.

Thanks for enriching the conversation.

Jesse,

This post inspires me.

First you helped me see that achievement is important but mastery is a priority for me. I had never known that about myself. Thank you.

I respect you and your work.

Best,

Dan

Hi Dan,

Thanks so much for taking the time to comment. I’m delighted that you learned something about yourself as a result of my post. I think it can be very helpful to pay attention to what types of goals you set (which genre). Most of us tend to hang out in one or two without realizing that others even exist.

I want to thank you for taking the time to read my post. I know it’s too long, but I just couldn’t figure out how to cut it down and get my essential message out. In fact I had more to say, but I cut an entire section out that I will save for another post in the future.

This is an amazing blog post. I like setting goals, but achieving them is not easy at all. I get frustrated sometimes, but on the whole, I’m happy if I accomplish more than half of my goals.

thanks for this reminder. It inspired me today. 🙂

Indeed! Setting goals is one thing. Achieving them is another. I hope the goals you accomplish are the ones that are most important to you. Thank you for your kind words and sharing your thoughts!

Jesse, I LOVE the GOAL GENRES. It explains a lot in terms of how I sometimes feel like I have to avoid the debate of MEASURABLE, as sometimes I can sound a bit “airy fairy”. I find my personal goals now are less quantifiable, but measurable based on the sense or feeling I get when I look at how I performed. Let’s just say presence eludes me less, so I am feeling good about that and I know there is more to get.

Hi Thabo,

I’m glad this post was helpful in confirming your instincts, Thabo. We can actually measure almost anything, but the question is, what measures matter? I think sometimes people forget (or don’t realize) that the role of goals is to enable the path. Even in business this gets fuzzy and we see the effect as a short-term focus with lack of coordinated efforts. It’s even more difficult on a personal level to remember what’s essential. The effect on a personal level is when someone achieves a goal, like purchasing a new Porsche, but it doesn’t bring the fulfillment they expected. Unfortunately, sometimes they just set another goal instead of taking the time to get clear on their priorities – their purpose, values and what it looks like when they are being lived on a daily basis.

The goal genre of Presence is especially difficult to understand unless you are having a direct experience of it. Otherwise, you need to draw on your memory of it, which is why I gave examples of when one might have had that experience. We really have no goals in that state, in the traditional sense, but rather respond to what arises as it becomes clear. And if we are not in that state, but desire it, we can have goals that support our reconnecting with it, as I listed a few examples.

A good place to start in the personal realm is to think about each of the Goal Genres and assess your current level of satisfaction. If something is missing, instead of then jumping to a solution and setting a goal, first ask yourself why you think that solution will bring more satisfaction. The answer to this question is much more elusive than setting a goal to purchase a new Porsche, but in the end will help you identify better goals, if any are needed.

My guess is you have an intuitive sense of this, which is why your personal goals are less quantifiable. It might be worth exploring whether there is something specifically needed. What are your hopes and dreams for your business, for your family and for your own personal fulfillment? In the end, I think the true measure is to what extent are you truly experiencing and appreciating your journey. (I’m not talking about instant gratification, but rather the experience of feeling alive and vibrant, which can be experienced in any emotional state).

It sounds like your approach is working. Presence eludes most of us when we try to achieve it, which is our typical approach to goals. But it is amazingly available when we pay attention to what’s happening in the moment.

Jesse,

Another really good and insightful post. The genres are really interesting — I had never thought to look through those lenses yet they make a lot of sense. One of the approaches I’ve had to goal setting came from the Management By Objectives work from George Ordione. You start with different “hats” you wear: Consultant, Business Developer, Learner, etc. Then you have objectives in each “hat” and by the time you’re through an overall goal has usually gotten clearer. I suspect any approach may work if you just sit down and write them….then post them like you suggest!

Hi Jake,

I agree that any model can be helpful, depending on how you use it. In fact it was George Odiorne who said it “should provide a framework for picturing the major factors in the situation as an integrated whole. It should be realistic. It should simplify the complex rather than complicate the simple.”

Without raising the MBO debate (e.g. Deming’s concerns), which is more about application rather than the system itself, I agree Odiome’s hats can be helpful for considering goals, depending on the context. My concern is the hats as you describe them are organized around identities rather than needs. When our identity is tied to a goal genre and that genre is no longer the most relevant, one is likely to experience a sense of confusion or identity crisis. I’m not sure Odiome’s hats would be as useful in that situation as it might interfere with the important process of dis-identification.

As always, thanks for digging into the content of this post and providing additional thoughts that extend and enhance it. Alternative models are always helpful. Because in the end, a model is only as useful as it is useful.

Hi Jesse ~ I have long felt myself somehow inadequate because I have rarely taken the time to capture my goals in any kind of concrete way. As a result, there were times when I felt that I didn’t really have any. Looking through the lens you offer, I can see that I have had many. And, there are many I am working on within the six genres you outline. Thank you for a truly thoughtful, and helpful, post.

Hi Gwyn, I am so glad that this way of looking at goals was helpful for you. It is truly amazing how strongly those “shoulds” can knock us for a loop. For many of us, myself included, the more we learn about best practices, the worse we feel when we aren’t doing what we think we should be doing, especially when we’re hanging out in the Mastery genre. The wonderful thing about the Presence Genre is those nasty little inner critics just don’t exist there. And actually, sometimes we don’t even notice that our goals have been realized because they have become integrated into our reality. There’s nothing left to measure because the goal itself has disappeared. I think we can best see the difference in how much we’ve move toward what we most desire when we “pause,” the topic of my winter solstice post.

Very well written and researched, Jesse. This is a very much a post that is worth some contemplation. I also think you added a very important caveat at the end. While I am a huge supporter of creating and driving towards goals, I personally need to be careful that I don’t turn my goals into projects and miss the experience of life. For me, it is important to remember that goals are a tool.

Micah Yost

Hi Micah, You hit the nail on the head. Goals are good, but we need to remember they are only a tool. It’s so easy to get so focused on our goals that we forget their role is to enhance our journey. Now that you are a new father, you are blessed by the opportunity to experience this lesson even more fully. It’s nice to see you here. Thanks for stopping by and sharing your wisdom.

Jesse, this “goals are a tool” theme Micah refers to and your own comment “the role of goals is to enable the path”! I am glad I came here to read properly. I have to write this down and marinate in it properly for it to become the essence of how I look at the objective. I feel like a kid with a new toy! AWESOME AHA MOMENT THIS!

Love those “Aha” moments! So glad to contribute to yours 🙂

Jesse-

I’m impressed you have twice remembered my life change of being a new dad! It is definitely giving new meaning to all sorts of things, including sleep! 🙂

I agree with Thabo, great lesson to remember here. (good to see you, Thabo!)

As I thought about this about more last night, I was reminded that it’s not only important to realize that there are these different areas we can have goals. As we work at becoming more “complete” people, it’s important that we have goals in all of these areas. I have been writing and studying recently on work/life balance and, in short, I have been advancing the idea that organizations need to be working towards creating happy and growing people, not simply happy and growing employees. How do you accomplish that? I’m not completely confident I have the entire answer at this point, but I suspect that this tool may be helpful. If an employer was to work at helping employees advance on goals in all of these areas they would surely be helping create more complete people and this must be good for both parties. Just some thoughts I had yesterday evening that I thought I would share.

Micah Yost

I agree with you completely about the importance of looking at work/life balance and especially appreciated your latest post on the subject Work/Life Balance is Nonsense. I like your idea of looking at employees as complete people, because in actuality, we shouldn’t have to hang part of ourselves on a hook when we enter the door to work. Organizations that create spaces where people can thrive can be financially successful as has been demonstrated by Zappos, Ben and Jerry’s, and Southwest Airlines to name a few. The Goal Genre model could be used as a tool to help managers think about the whole person and not just the employee aspect. An interesting thought.

Jesse,

Thank you for reminding me to be present, and to be in a positive presence. That is, rather than what I need to do or what is lacking, what is good. Where am I in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs? I am thankful that I meet basic needs of survival as a base, and rise up the hierarchy towards self-actualization. Perhaps being able to self-actualize is the ability to take the moments to be in the present.

Another theory to consider is Erik Erikson’s 8 stages. The 8th stage is ego integrity – looking at what one has done over life course, and being satisfied. While he talks about stages across a lifespan, and this is for those who used to be older and now are middle age 🙂 with some life experience we can use this lesson too.

Neither of these mean that we don’t form new goals, future plans or engage in meaningful activities.

As a work tool, it brings to mind the “To Do” list, and how I relish checking off completed tasks. Sometimes I feel my “To Do” never ends, and each task accomplished brings two more. I work in a people industry, and am often mindful of the impact we have on people’s lives. I sometimes feel I could work 24/7 and never be done. This blog highlights that in order to do our best, we need moments of presence – on the job and away. How can we prioritize our “to do” lists? ? Or do we need an other sort of list, or way to view our work? You caution about making Presence into a project, but I am going to think about how to make concrete tasks that must be done into ones that satisfy Presence.

Thanks, Jesse, for encouraging me to think in different ways!

Hi Ann,

Wonderful reflections! How does the ability to take in the moment fit with the realities of our busy lives? – a really important question. I appreciate your mention of Erikson. I think it is a helpful to consider the stages of human development, especially as you point out, as we become older and look back on our real experiences.

Ultimately, the question is how do we integrate what is most pressing for us in each moment with the opportunity to truly experience the moment – again, a question that becomes even more relevant as we become older and begin to really understand the finality of our lives, something that seems more theoretical when we’re younger (e.g. yes, I know it, but I don’t really believe it).

I think it’s a wonderful idea to consider how to make the concrete tasks that must be done into ones that satisfy Presence. I wonder if a clue might be in integrating the “how” with the “what” – can you approach your tasks in a way that is more mindful of the present. Personally, I find it most challenging when I am really busy. I just have to slow down or I get lost in “To Do” land. Thanks so much, Ann, for sharing your own thinking and reflections, and I look forward to hearing what you find out in our own continued explorations.